When I was in eighth grade working on my first family tree, the EMC librarian told me that I wouldn’t find any information on Brocks Gap families. A lot has changed since then. Now most of the Gap families have at least a chapter or two published about them.

However, one group of people has been missing from the records—African Americans in Brocks Gap. That’s right—there were both free and enslaved African Americans in the Gap until 1865. I found enough information to author a book, African Americans in Brocks Gap, Rockingham County, Virginia.

My pre-conceived ideas about slavery were busted. I thought there would be few slaveholders in the Gap; instead, at least 31 different people were slaveholders. I thought enslaved persons would only be used as extra farm hands; instead, they were used like a cash crop with children being sold away for profit. I hoped that enslaved people would have been treated like family, but we really can’t know how they were treated. I thought only one or two of my ancestors had been slaveholders, but I am related to all 31 slave holders. Enslaved people like Jack, Sarah, Peggy Jones, and Samuel Dove are part of my family’s stories. I was able to learn some details for just a few of the enslaved.

One of the wealthiest men in the Gap, Michael Baker 1747-1803 was not taxed for enslaved people. After his death in 1803, his sons evidently purchased at least 3 or 4 slaves, and his widow Elizabeth purchased “a negro girl” in 1817 for $275. Elizabeth died in 1824, and in her will freed Peggy Jones. Peggy’s 1827 emancipation certificate describes her as “a Very dark Mulatto Woman Five Feet Three Inches high about Thirty Four Years of Age and has a Small Scar above the Right Eye…” Another Baker slave named Bob was set free in 1817 and was described as 32 years of age, “five feet Eleven inches high a Bright Mulletto [sic]… is a S[t]out able-Bodied Man.” I don’t know what happened to Bob or to Peggy Jones after freedom.

My ancestor George Dove ca 1760-1831 was a community leader and slaveholder, first taxed for one enslaved person in 1812 and with six in 1820. His home was on German River at now Bergton. In 1822-23, George was elected as Rockingham County’s High Sheriff whose main duty was collecting taxes, for which he’d receive a 6% commission. To back his financial obligations as High Sheriff, George had to post a bond of $30,000. In 1823, George mortgaged his entire estate, which included 7 enslaved people. During his second term, there was an irregularity (I think one of his deputies took off with the taxes he had collected), and George had to make up for the taxes that were not collected. That meant selling his enslaved people Areno, and her young children Edmond, Maria, Kessia, Samuel, and Peggy.

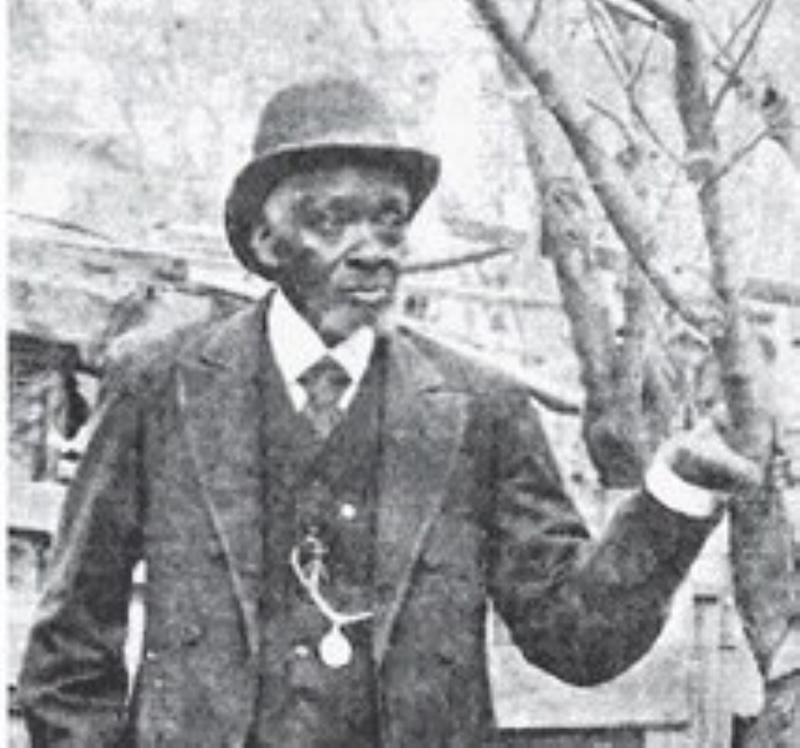

By several coincidences, we found Samuel Dove’s life’s history in a Utica, NY newspaper. The article quotes Samuel: “I do not know what my father’s name was. I don’t remember anything about him, as he was drowned when I was a little ‘shaver’ and when I was 10 years old I was sold as a slave to a man named George Dove, High Sheriff of the State. From him I got the name that has always clung to me. I did not remain long the property of the Sheriff, as he had to sell his (slaves) to pay his debts. He sold my mother, brother, two sisters and myself and kept one sister. We were torn from each other’s arms. I was put up in the market in Richmond, Va. I brought $350, being purchased by a man named Joseph Meek.”

After being sold away from his family in Richmond, Samuel was taken to Tennessee where he learned the blacksmith trade. In the 1850s, he went to Utica, NY with his master John Munn, but refused to return to Mississippi as a slave when Munn moved back. Samuel and his wife remained in Utica where they made a living and owned a home. They had to buy their own son from Munn. Unfortunately, their son died just over a year after reuniting with them in New York. Samuel was a volunteer firefighter in Utica before he died in 1904. In 2016, the City of Utica put a wreath on his grave to honor his firefighting service.

It is perhaps fitting that former slave Samuel Dove, who has no living relatives, has a large tombstone and was honored 100 years after his death for his service, while his former master George Dove, with thousands of living descendants, lies in an unmarked grave in the family cemetery.