“We used to hear them sing as they rode down the street on their way to work,” says Bonnie Showalter, remembering those two summers long ago when young German Prisoners of War were based in Timberville.

This influx of young men was a novelty for Bonnie and her friends. Her uncle owned Gordon’s garage; on weekends, he’d clear out a space for the young people to play games and hold dances. The POW guards were invited and often attended these gatherings on their off duty hours. This event, organized by Mrs. Paige Gordon, involved three local churches (Trinity UCC, Timberville Church of the Brethren, and Rader’s Lutheran). They created these social opportunities so “they’d know what we were really like as a community,” says Bonnie. The church group offered coffee, soft drinks, writing materials, and music.

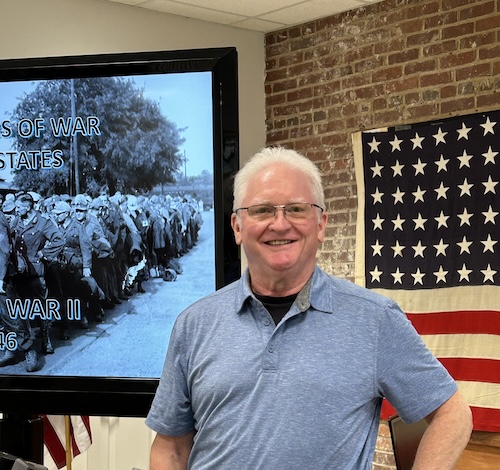

However, according to Greg Owen, a historian and author, communities were not always welcoming. “At first, there was a lot of fear and resentment when the POWs entered our civilian workforce.” After all, these newcomers were part of the enemy force. Would communities be safe?

The first big question that comes up, however, is why the US government saw fit to use POW labor. World War II is considered the most significant event of the 20th century. 70 nations were involved, and nearly 80 million people died—both civilian and military.

The number of people who served in the military or were involved in war production took a huge toll on the U.S. Labor force. This labor crisis created an unexpected predicament. There were no longer enough people to take care of the jobs back home. Farms, orchards, poultry production, and manufacturing companies suffered from a lack of laborers.

The other issue the US faced was the growing population of Prisoners of War.

This double dilemma forced the US Government to create a program with no precedent. At no time in the country’s history did the US have so many people involved in war and war production, and at no time in our history had there been such a massive number of POWs on US soil.

The Federal Government soon realized it could not tackle this project alone. It needed help from the War Department, the State Department, and local agencies. With a carefully planned, meticulously thought-out strategy, both the labor shortage and the difficulty of managing the huge population of POWs could be solved.

According to Greg Owen, local farm and business people met with USDA and county farm Extension Service Agents to discuss local labor needs. The County Agents then submitted a Certification of Need to the War Manpower Commission to attest that no other source of civilian labor was available. When the POW Branch Camp Commander approved requests from local employers. Frederick Holsinger was the County Extension Agent for the Timberville area.

Although most local communities came to accept the POW labor camps, many were resentful and afraid at the onset of the program. When they began to see, however, that the POW labor force was essential to saving crops and helping businesses run smoothly during the war years, they realized the extra help was truly needed.

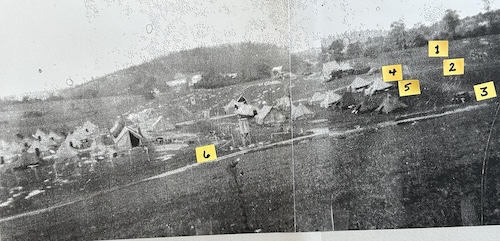

There were 35 base camps and branch camps in Virginia. Camp Timberville and Camp Lyndhurst in Augusta County housed POWs. Timberville’s camp was a tent camp, and Lyndhurst used an abandoned CCC camp. According to the 1929 Geneva Convention, POWs were to be treated the same as the guards, so both POWs and officers slept in the same accommodations. Owen said that localities were careful to follow the Geneva Convention laws concerning POWs so countries holding US Prisoners of War would have no grounds to mistreat their captives.

According to Owen, German and Italian diplomats were housed at the Ingleside Hotel in Staunton and the Shenvalee Hotel in New Market. When Italy surrendered before the war ended, the Italian diplomats were separated from the German diplomats. The Italians were moved to New Market, and the Germans stayed in Staunton. Rumors have it that the handsome Italian men caused quite a few hearts to flutter in New Market and surrounding towns.

The Timberville camp was set on Herman Hollar’s farm on Route 881 about two and a half miles west of Timberville. The POWs were here for three months during the summer of 1944 and 3 months during the summer of 1945. After leaving Timberville, they were taken back to Camp Pickett.

Local residents, brothers Ben and Joe May, watched the construction of the camp from a hill above the area. “We were hoping for some action,” says Ben. But no “action” happened. The transition went smoothly enough. Rumor has it that one POW noted that when they rode into Timberville, folks stared at them, “trying to see if we had horns.”

However, Timberville residents soon realized that their families and these men shared more similarities than differences. The POWs were an essential part of food production. Their work was critically important. In July 1944, 350 train cars of food were shipped out of Timberville, and in June 1945, 280 cars full of food were shipped. Much of the food production was the result of POW labor.

Locally, POWs worked for Ziegler Cannery, Rockingham Poultry, Mutual Cold Storage, and the H.E. Mason Sawmill. Some worked in Harrisonburg at Rocco, City Produce Exchange, Tip Top Fruit Farm, and Harrisonburg Junk and Hide. POWs traveled between Timberville and Harrisonburg via bus. Farmers were responsible for their workers’ transport.

Owen says the average daily wage at the time was $2.85 per day, and that’s what business owners were required to pay their POW workers. .85 cents of that money went directly to the workers in the form of a “canteen script” –a certificate that allowed them to purchase razors, candy bars, and other novelties that made their stay more pleasant. Any money they didn’t spend was given to them by check after the war ended. Owen says that money helped many POWs survive when returning to Germany.

World War II was, indeed, a time like no other. The war-related lack of a US labor force and the abundance of Prisoners of War was a double-edged dilemma that had never been faced before. The POW work program’s successful outcome is evidence that we can accomplish difficult things by working together. Although hiring thousands of enemy prisoners to work in civilian jobs was daunting, the outcome was mutually beneficial. The success of the program far outweighed the security risks. And many Timberville residents have fond memories of the unlikely relationships they formed during the strange days of World War II.

Labels for the map in the photos:

- Guard Compound

- Main Entrance

- Van to transport POWs

- Mess

- Latrine

- Barbed wire fence