Our grandparents would scoff at today’s easy life. For instance, my laundry day means tossing clothes in the washer, adding detergent, and pushing a button. My grandmothers in the early 1900s carried water from the river and boiled clothes in large outdoor kettles, after they had made their own lye soap from fat saved from cooking.

Likewise, my grandfathers had a more strenuous lifestyle. My grandfather Bill Albrite 1882-1963 was a farmer who never owned a tractor. His family lived off the land in many ways. Groundhog meat was a frequent supper entrée, and he tanned their hides to make leather shoelaces. One heavy job he performed was burning limestone to make lime to enrich the farm soil. Limestone rocks and wood for firing were plentiful on his farm, so there was no cash outlay for lime.

My mom Lena Albrite Turner 1930-2015 described the process: “In the present we can purchase lime in various size bags for our needs. This was not an option in [her grandmother] Ma’s life. Several farmers cooperated to make lime for use in white wash or fertilizer. A temporary kiln was constructed, filled with limestone and fired constantly for the prescribed time—could be for several days and nights.”

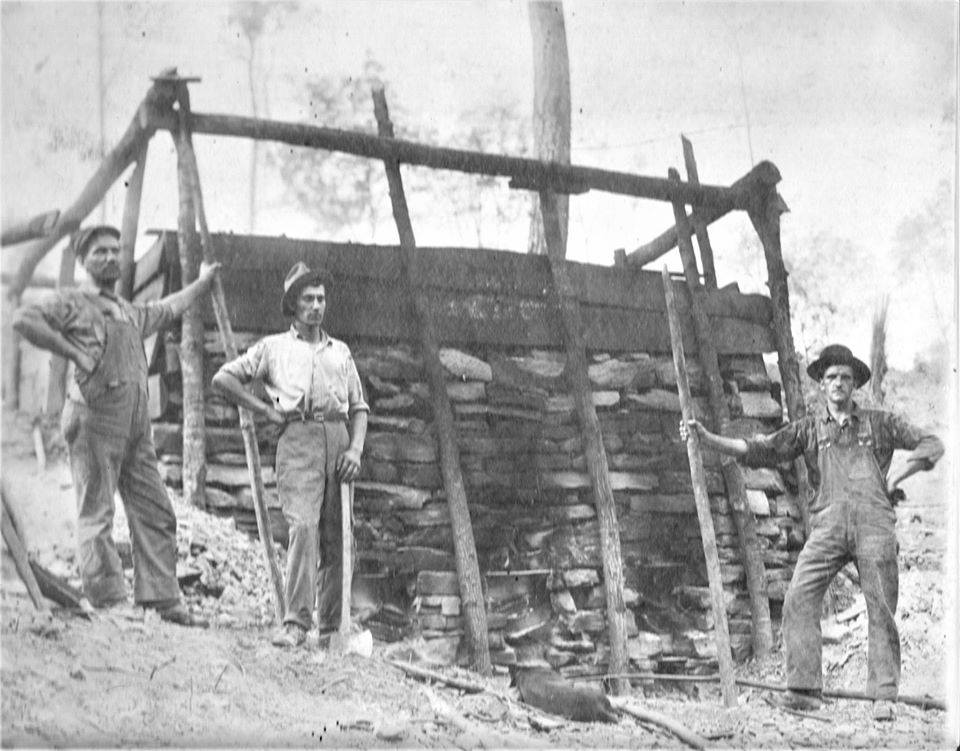

Wade Fawley, Davy Fawley and others built a temporary kiln on Grindstone Mountain; in 2004 you could still see its location as a slight depression along the mountain road. It wasn’t a big commercial stone kiln but was probably more like the Hardy County kiln in the photo shared by cousin Carol Westfall. The kiln had to be fired to a high temperature for several days and nights to reduce the limestone rocks to lime. It took skill to make lime successfully. If the fire burned too hot, the limestone melted. If the fire was not hot enough, the limestones would not be completely burned.

The burnings were sometimes a social gathering. My aunt Lettie Albrite 1906-1998 recalled that people would gather to bake potatoes in the hot coals. Folks sometimes threw in sandstone rocks to become glazed during the heating process. My great-grandparents used a glazed one as a doorstop.

Lime rejuvenates poor soil and increases crop yields. Not all farmers in early days knew that. My ancestor James Turner II 1765-1849 had been a farmer in Fulks Run for over 40 years when he received a letter about the advantages of liming the crop fields. A friend from Carroll County, MD wrote to James, explaining that he heard James’ farm was “farmed down.” He offered to come to Turner’s farm and show him how to make a lime kiln. “You have limestone so handy and plenty that you can get them for nothing,” he pointed out, whereas in Maryland it cost about $30 to $60 to purchase limestone to burn. “You can make your land worth from $20 to $30 per acre” in two or three years by liming it,” the man wrote. “What is the use to have land and pay the tax of it and can’t raise nothing.” He offered to bring a mason and come to Turner’s farm to build a kiln for $60 that would hold 600 bushels. It would be a bargain for Turner, because the total cost of boarding the builder and mason, hauling the rocks, and digging the kiln would be cheaper than just the rock purchase if he lived in Maryland. The letter sounds as if he was proposing building a permanent stone kiln, not a temporary one.

Did James Turner accept the offer? I don’t know. The Turner farm is still owned today by his descendants, and maybe they know locations of old kilns on the property.

Brocks Gap native Solomon Custer 1852-1905 moved to Dale Enterprise. On January 29, 1885, the local newspaper reported “Solomon Custer is redeeming his time during the present season by putting up a lime kiln, so as to be ready for action when the season opens.” On August 27, 1885, “Solomon Custer completed the burning of a large lime kiln on last Saturday night. He expects to use the lime to enrich his land.” It sounds as if Solomon was making lime for his personal use.

Lime had other uses. Lena recalled that “white washing buildings and fences was another chore. Since paint was not readily available and money was scarce, this home-mixed solution was used to preserve the wood and to “spruce” up the area around the home. Lime was the main ingredient mixed with water. I think there was whitener added, but I am not sure. This solution was not kind to human skin!”

For more technical information on kilns, search for “Lime a Staple of Life in Earlier Times” in lancasterfarming.com.