This wasn’t the first time. In the early 1940s, Lloyd Turner (Garnett’s father) and other Fulks Run residents took a bus to Congress and convinced a committee not to build a proposed Brocks Gap dam. But that was during WWII, when there were other priorities.

By the 1960s, rapid development around metropolitan Washington prompted the Army Corp to design a series of dams up the Potomac River and into the Shenandoah Valley. The Brocks Gap dam would hold 61 billion gallons of water, to be drawn down as needed to dilute pollutants and sewage discharged by industries and municipalities downstream. It would also, the Corp wrote in its report, provide flood control plus recreational swimming and boating areas for at least 200,000 visitors annually, and still – somehow – preserve drinking water quality. “I remember when the Brocks Gap Dam was being discussed,” said Tammy Cullers (native of Fulks Run and editor of this paper). “I was a very young child, but the thought terrified me!”

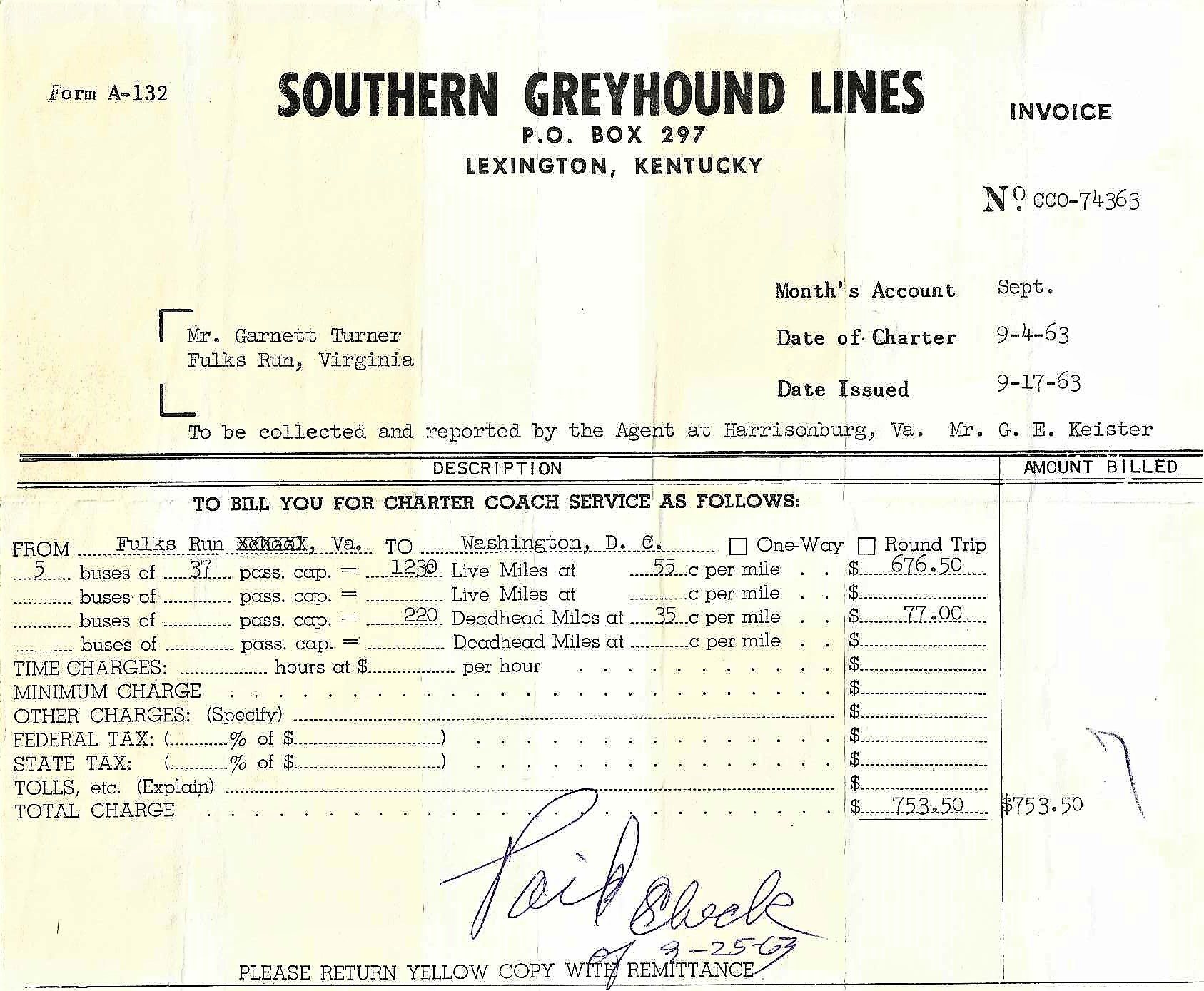

Garnet Turner and the Fulks Run Ruritans organized the bus trip. Herman Turner, a Fulks Run native and owner of Turner Electric Company in Timberville, was the spokesman. He included the text of his speech in his 1998 book, The Turner Mill. In it, he rebutted the Army Corp’s many errors, such as the undercount of families to be moved (120 to the actual 312). “A closely knit farm community would have to be moved,” he said. Where to? Would the land be taken from others? “We do not appreciate the methods used by the Corps,” he continued. “They are using our tax money [for] … unfair and unjust methods.”

He also referenced studies that showed how building a number of small headwater reservoirs on various streams would offer many of the same benefits without such immense destruction. “Some of the recommended sites are located on national forest land,” he pointed out, where no one lived.The group’s compelling presentation to Congress was followed up by several more years of community meetings in the newly built Fulks Run Elementary School, and letter writing and local lobbying by the Fulks Run Ruritan Club. By 1968, several small dams had been approved. After more years of studies and permits, dams at Lagoha on the Shoemaker River and on two of its tributaries in the George Washington National Forest, Slate Lick Branch and Hog Pen Run, were built. No one was forced to move.