Last month’s column introduced Light in August, Faulkner’s most readable major novel. Two other of his novels, however, are more famous: The Sound and the Fury (1929) and Absalom, Absalom! (1936), arguably his greatest novel. Both novels feature stream-of-consciousness narration, a technique that makes these novels harder to read than Light in August. Both novels, however, again deal with family trauma, but families in these novel are higher on the social scale than those in Light in August.

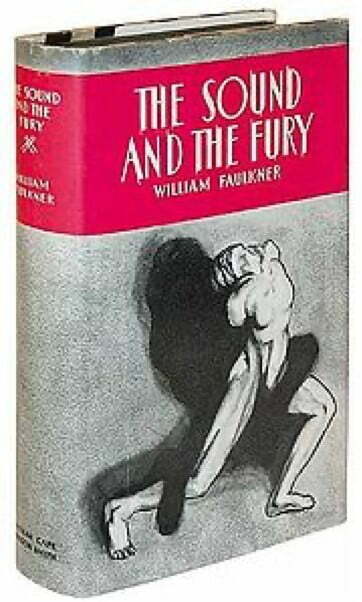

The Sound and the Fury presents the Compson family in Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha Country in the late 1920s; the family is one of long standing in Mississippi, but their social influence has declined. The title of the novel, derived from one of the most negative passages in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, reflects the negativity in the Compson family: the parents and their four children seem fated for ruin.

Faulkner structures the novel with four sections, three of them focused on Compson children; the fourth is a third-person narrative. Faulkner’s use of the stream-of-consciousness technique reveals the suffering of two of the brothers, Benjy and Quentin. A third brother, Jason, narrates a slanted version of the family’s history. A final section centered on Dilsey, the stalwart servant of the family, reveals the most direct history of the Compsons. Caddie, the one daughter in the family, though so much the center of her brother’s lives, gets no narrative perspective. Each of the Compson brothers is an unreliable narrator, limited in various ways.

For a first-time reader, Benjy’s section of the novel will seem most confusing. Benjy, just past thirty in the immediate present of the novel, is so intellectually limited that he has never said a word; however, he has vivid memories of multiple episodes from his family’s history; his mind operates in flashes so that a word in one memory triggers his recall of an earlier or later event. Faulkner originally hoped to print each of these memories in a different color of ink, but in 1929 that was clearly impossible. Instead he used a combination of direct print and italics to trigger the vacillation of Benjy’s memories. Readers will gradually be able to follow that pattern.

Quentin’s section is actually more complex than Benjy’s: a freshman at Harvard, Quentin, remains intensely troubled by his early experiences. Both highly intelligent and deeply sensitive, Quention examines the problems both of the Compson family and of the South in general. He can solve none of these family and cultural traumas.

A professor at the University of Virginia once termed Quentin’s brother, Jason, “the meanest man in American literature.” And he probably is. Motivated by greed and jealousy, Jason is unable to tell the family story with any semblance of reality. His opening comment about his sister Caddy and her now-teenaged daughter (also named Quentin) tells everything we need to know about Jason’s family crudity : “Once a bitch always a bitch, what I say.”

Having completed the first three sections of the novel, Faulkner decided that he needed to clarify; he subsequently wrote the third-person Dilsey narrative. Her stance clearly shows how the family has fallen into ruin. Armed with her religious faith, she, an outsider, offers the only hope in the novel.

Family issues continue to be of importance in Absalom, Absalom! in which two of the Compsons are also major characters, Quentin and his father Jason. But through Thomas Sutpen, Faulkner achieves a broader focus. The title of this novel alludes to the Biblical Absalom and his family problems, but the real center of the novel lies with Thomas Sutpen as a traditional quester, who looks to achieve transcendent success in a world in which his kind of striving is futile. His evolves as a 19th-century version of Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby. Faulkner uses three unreliable narrators to present his convoluted history; thus, the reader must become the final interpreter of Sutpen’s epic story.

Faulkner creates a wave-like pattern in the narrations in Absalom, Absalom! They back up on each other and create in the reader a tension that he never fully resolves–such is the reality of human existence. Quentin Compson’s loquacious fathe is one narrator: his story is unreliable because it is second-hand, based on stories that his own father, a contemporary of Thomas Sutpen, related to him over the years. Jason Compson’s embellishments further confuse his son and the reader.

The second narrator, the elderly Rosa Coldfield, had a personal connection with Sutpen. Her tellling evolves from intense anger. Her sister was married to Sutpen and after she dies, Sutpen proposes marriage to Rosa, predicated on her ability to produce a male heir to replace the sons he has lost. Totally insulted by the proposal, Rosa feeds off her hatred of him and thus tells a warped version of his history.

Quentin Compson, a freshman at Harvard, becomes the unwilling confidante of Rosa Coldfield; on the basis of her story and his father’s tales, Quentin and his roommate Shreve function as the final narrators. Their imaginative genuine adds many details to the Sutpen story, but the reader cannot trust their final creative version. Their conclusions provide few solid answers. In this respect the novel becomes an almost post-modern statement about the human inability to understand the inexplicable nature of life. Despite the difficulties and darkness Faulkner presents in these two novels, they are definitely worth reading.

Jean W. Cash, Professor of English, Emerita

James Madison University