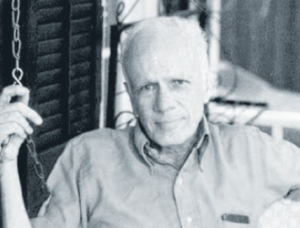

Walker Percy (1916-1990) occupies a position in Southern Literature quite different from that of William Faulkner or Eudora Welty. In focus, he is more like Flannery O’Connor; a Catholic convert, he wrote about contemporary seekers like himself who look to achieve transcendent meaning in a world mainly bereft of religious feeling.

Percy’s background is somewhat different from that of the others. He was born in Alabama into a wealthy Mississippi family with roots deeply embedded in both British and American culture. He is also different from the others in that his first interest was in philosophy; he published essays before his first and most famous novel The Moviegoer came out in 1961, winning the National Book Award over both Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and J. D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey. Though he and O’Connor had not yet met only, she wrote to congratulate Percy on the award.

Suicide seemed to run in the Percy family; his grandfather LeRoy Percy, a Mississippi politician, committed suicide in 1917, and Percy’s father killed himself in 1929. Two years later near Leland, Mississippi, his mother drove her car off the road, killing herself. Percy thought she, too, had committed suicide. Percy’s life improved, however, when he and his two younger brothers were taken in by their second cousin, William Alexander Percy, a wealthy lawyer and poet from Greenville, Mississippi. As a teenager in Greenville, Percy met many literary figures who were friends of his cousin, among them William Faulkner. Percy also met Shelby Foote, a native of Greenville, who became his lifelong best friends. You may remember Foote’s commentary in Ken Burns’s Civil War series.

After high school in Greenville, Percy and Foote attended the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Percy was a pre-med student, but he also wrote essays and book reviews for the Carolina Magazine, the university’s literary magazine. Percy graduated in 1937.

From there he went to med school at Columbia, University; he planned to become a psychiatrist, but gave up that specialty after three years. Working as an intern at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan in 1942, Percy contracted tuberculosis from a cadaver on which he was performing an autopsy. His illness forced him to give up the idea of becoming a doctor.

Treated in a sanatorium in upstate New York, Percy began to read widely, developing a special interest in the work of Soren Kierkegaard, the Danish existentialist. He also read Dostoevsky, Jean-Paul Sartre, Franz Kafka, and Thomas Mann. Though raised as an agnostic in William Alexander Percy’s home, Percy, during his recovery, turned to Roman Catholicism and began to attend Mass daily.

Throughout his life Percy was supported by his inheritance from William Alexander Percy who died in 1942. Percy began to write fiction in the late 1940s, producing two novel he never published, but gaining the support and encouragement of Caroline Gordon and others. He published The Moviegoer in 1961 after years of writing and re-working the novel. Six additional novels followed: The Last Gentleman (1966), Love in the Ruins (1971), Lancelot (1977),The Second Coming (1980), and The Thanatos Syndrome (1987). Percy also published two collections of essays. Besides the National Book Award, Percy received major awards from both Saint Louis University and the University of Notre Dame. In 1989, chosen by the National Endowment for the Humanities, he gave the Jefferson Lecture at the Library of Congress, titled “The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault in the Modern Mind.”

Percy married a nurse, Mary Bernice Townsend; they officially joined the Roman Catholic Church in 1947. After they settled in Covington, Louisiana, they adopted one daughter and conceived a second who became deaf early in her life. Her illness sparked his interest in language. While living in Covington, Percy taught periodically at Loyola University of New Orleans. Approached by John Kennedy Toole’s mother, Percy was mainly responsible for getting Toole’s posthumous novel, A Confederacy of Dunces published in 1980. Percy died in Covington in 1989 from advanced prostate cancer. Shelby Foote was at his bedside.

1. The Moviegoer is a novel much different from those of Faulker, Welty and O’Connor. It is an intensely modern novel. Percy himself described it as the story “of a young man who had all the advantages of a cultivated old-line southern family: a feel for science and art, a liking for girls, sports cars, and the ordinary things of the culture, but who nevertheless feels himself quite alienated from both worlds, the old South and the new America.”

Approaching thirty, John Bickerson Dowling, has little sense of who he is and how he can survive in a world he cannot understand. Among the people around him, he is known by various names–John, Jack, Binx–through which Percy emphasizes his character’s lack of identity. Binx is a Approaching thirty, John Bickerson Dowling, has little sense of who he is and how he can survive in a world he cannot understand. Among the people around him, he is known by various names–John, Jack, Binx–through which Percy emphasizes his character’s lack of identity. Binx is a partly autobiographical character, one who shares Percy’s loss of his father, his elitist background, his college experience, and his early quest for spiritual certainty.

Binx has managed to carve out a half-satisfactory adjustment to life in New Orleans where he has been partly raised by his Aunt Emily, a female version of Percy’s foster father, William Alexander Percy. Binix enjoys making money in his Uncle’s brokerage business, dallies with his attractive secretaries, and sees countless movies, whose exaggerated heroes provide him a kind of substitute life. When none of these pursuits really satisfy Binx ,he decides to conduct a genuine search for what Paul Tillich termed “ultimate reality.” Early, he asserts that his search may be for God. Percy follows Binx’s Search, but because he {Percy) is unable to preach O’Connor’s brand of Catholic certainty, his character’s ultimate conclusion is at best tentative. Only by reading The Second Coming (1980) can the reader discover Percy’s final outlook on God.